Obras de referência da cultura portuguesa

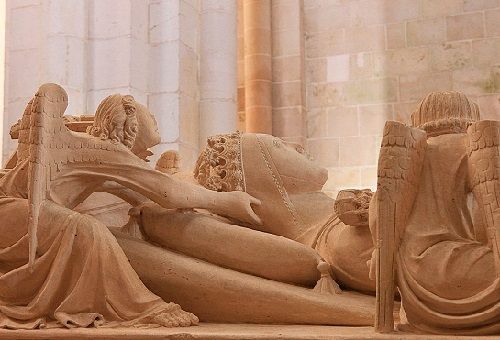

"CASTRO"

de ANTÓNIO FERREIRA

Análise de Duarte Ivo Cruz

Tradução de Alexandra Leitão

Diremos que Castro de António Ferreira é uma das referencias basilares e indiscutíveis da dramaturgia portuguesa, e isto tanto no plano do texto, como do espetáculo e como ainda do próprio conteúdo histórico e cultural. Com a especificidade de constituir a primeira grande peça a partir de um dos temas de maior profundidade e universalidade da cultura e da mentalidade portuguesa.

A Castro acumula peculiaridades de feitura que mais a singularizam. Desde logo, porque segue a corrente dominante na época, de utilização da tragédia como expressão didática a nível universitário. Só que o lente da Universidade de Coimbra António Ferreira inovou na escolha de um tema português e na utilização de uma fórmula teatral admirável de equilíbrio, de qualidade e de modernidade.

E tudo isto, no que se refere ao texto em si, pela conciliação extremamente moderna, para a época e para a nossa época, da gravidade formal da tragédia e da força irresistível do amor e da paixão - desde logo da paixão dos dois amantes, mas também do amor da mãe pelos filhos, do avô pelos netos e até da dedicação dos servidores-coreutas. Essa força do amor e da paixão é aliás invocada para justificar a execução de Inês.

Diz o Rei: "Manda-la-ei deste Reino". E diz o Conselheiro: "o amor voa / Este fogo, Senhor, não morre logo".

Mas a paixão não se passa em cena. Mais: os dois amantes nunca se encontram em cena, para grande aflição dos dramaturgos românticos e mesmo dos pré-românticos, se como tal quisermos considerar o árcade Quita que justamente tem em A Castro, publicada em 1766, quase exatos dois séculos depois da data previsível da tragédia de Ferreira, a sua melhor peça. Mas insista-se: a tragédia de Ferreira continua exemplar de força e modernidade na caracterização do "grande desvario" de Pedro e Inês.

Depois, há o interesse de Estado, que podemos interpretar ou não numa base de isenção pelo bem comum e pelas prioridades do desígnio nacional de independência face ao poder de Castela. Aí, surge a argumentação cruzada do Rei e dos Conselheiros, que abordaremos a seguir noutra perspetiva, mas que sobressai, aqui, numa opção política bem ou mal fundamentada no interesse da "república" no sentido clássico do termo.

Ouçamos alternadamente o Rei (R) e Pacheco (P):

"(R) - Mal parece matar uma inocente / (P) - Não é mal: que a causa o justifica / (R) - Antes Deus quer / que se perdoe um mau, que um bom padeça. / (P) - Este teu corpo / de que tu és cabeça, está em perigo / por esta mulher só (...) Médico Senhor és desta Republica / O poder, que tem o Médico num corpo, tens tu sobre todos nós: usa dele".

Mas esta situação comporta ainda um interessantíssimo problema a nível de mentalidade. É que grande parte da cena consiste precisamente na argumentação cruzada do Rei, que avança com argumentos e alternativas à execução de Inês, e a intransigência dos Conselheiros, que insistem, contrariam os argumentos do Rei e acabam por vencer ou convencer o Rei. Ora bem: a mentalidade renascentista, ainda por cima analisada por um Lente de Leis, comportaria um debate desta natureza. Mas seria o Rei medieval D. Afonso IV o Bravo suscetível de ser convencido pelos conselheiros, se quisesse ou não executar a mãe dos seus netos?

E reconheceria esse Rei medieval a tragédia da solidão do poder? E é uma vez mais o professor de Direito do séc. XVII que nos deixa essa meditação extremamente atual em si mesma: "Rei - Oh cetro rico, a quem te não conhece, / Como és formoso e belo! e quem soubesse / Bem quão diferente és do que prometes, / neste chão que te achasse, quereria / Pisar-te antes cos pés, que levantar-te. / não louvo os que se louvam por impérios / A ferro, sangue e fogo destruíram / O seu próprio estendendo"...

Justamente: o melhor exemplo da modernidade da Castro de António Ferreira está, além da beleza clássica do texto, na extraordinária potencialidade de espetáculo dos diálogos. Fique como síntese final a cena do convencimento do Rei pelos Conselheiros.

"Rei - Ela que culpa tem? / Pacheco - dá ocasião. / Rei - Oh que ela não a dá, o Infante a toma. / Que lei há que a condene, ou que justiça? / Conselheiro - O bem comum, Senhor, tem tais larguezas / com que justifica obras duvidosas / Rei - Assi que assentais nisto? / Conselheiro - Nisto. Morra / Pacheco - Morra / Rei - uma inocente? / Conselheiro - que nos mata! / Rei - Não haverá outro meio? / Pacheco - Não o temos / Rei - Metê-la-ei num convento / Conselheiro - Ei-lo queimado"...

CASTRO by ANTÓNIO FERREIRA

Castro by António Ferreira is one of the fundamental, indisputable references of Portuguese dramaturgy, both from the point of view of the text, of the play itself and of its very historical and cultural content. It is also the first major play based on one of the profoundest and most universal themes of Portuguese culture and mentality.

Castro is also remarkable for the originality of its structure. Firstly, because it follows the dominant current of the time, which was to use tragedy as a didactic expression at university level. António Ferreira, who taught at the University of Coimbra, was nevertheless innovative in his choice of a Portuguese theme and in the use of a theatrical formula that is admirable for its equilibrium, quality and modernity.

As far as the actual text is concerned, this is achieved by a reconcilement that for its time and even for our time is extremely modern, between the formal gravity of the tragedy and the irresistible force of love and passion – firstly, the passion of two lovers but also the love of a mother for her children, that of a grandfather for his grandchildren and even the dedication of the attendant chorus. It is a force of love and of passion that is in fact invoked to justify Inês’s execution.

The King says: “I shall have her banished from this kingdom”. And the counsellor says: “Love flies / This fire, Sire, will not die so soon”.

The passion is not paraded on stage. In fact, the two lovers never meet on stage, to the great distress of the Romantic and even the pre-Romantic playwrights, if we so wish to consider the Arcadian Quita, whose best play, published in 1766, almost precisely two centuries after the date of Ferreira’s tragedy, is Castro. However, we insist: Ferreira’s tragedy endures as an example of strength and modernity in its characterisation of the “great madness” of Pedro and Inês.

Then, of course, there is the interest of State, which we can interpret or not as being impartial as regards the common good and the priorities of the national objective of independence from the power of Castile. There, we see the arguments exchanged between the King and his counsellors, which below we will look at from another viewpoint, although highlighted here as a good or a bad political option from the point of view of the res publica or the public thing, in the classic meaning of the word.

Let us listen in turn to the King (K) and to Pacheco (P):

“(K) – It seems wrong to kill an innocent woman / (P) - It is not wrong: the cause so justifies it / (K) - God would rather / we forgave a bad man than let a good man suffer. / (P) – This body / of which you are the head, is in danger / because of this woman alone (...) Sire, you are the doctor of this Republic / The power a doctor has over a body you have over us all: use it".

This situation also contains a most interesting problem in terms of mentality. Most of this scene consists precisely of the exchanges between the King and his counsellors; the King puts forward arguments against and alternatives to the execution of Inês, whilst the counsellors demonstrate their obduracy, by insisting, contradicting the King’s arguments and eventually defeating or convincing the King. Now, the Renaissance mentality, particularly as analysed by a professor of law, could comprise a debate of this nature. However, was it likely that the medieval king, Afonso IV, known as the Brave, would be convinced by his counsellors as to whether or not he wished to execute the mother of his grandchildren?

And would this medieval king recognise the tragedy of the loneliness of power? Once again, it is the 17th century professor of law who leaves us with this extremely contemporary meditation: "King - Oh rich sceptre, did we not know you / You would appear lovely and beautiful! As we do / How different you are to what you promise / on the ground where I found you I would rather / trample you with my feet than pick you up. / I do not praise those who praise themselves for using empires / Destroyed by iron, fire, and blood / to extend their own "...

Precisely: the best example of the modernity of Castro, by António Ferreira, lies not in the classical beauty of the text but in the extraordinary potential of the spectacularity of the dialogues. Let us present as our final summary the scene where the King is finally convinced by his counsellors:

"King – What is her fault? / Pacheco – she seizes occasions. / King – Oh, she does not, the prince does. / What law or justice will condemn her? / Counsellor – The common good, Sire, has such largesse as to justify doubtful works / King – So you agree to this? / Counsellor – Yes. Let her die / Pacheco – Let her die / King – an innocent woman? / Counsellor – who will kill us! / King – Is there no other way? / Pacheco - No / King - put her in a convent / Counsellor – It will burn"...

Obras de Referência da Cultura Portuguesa

projeto desenvolvido pelo Centro Nacional de Cultura

com o apoio do Ministério da Cultura

Divulgue aqui os seus eventos

Divulgue aqui os seus eventos