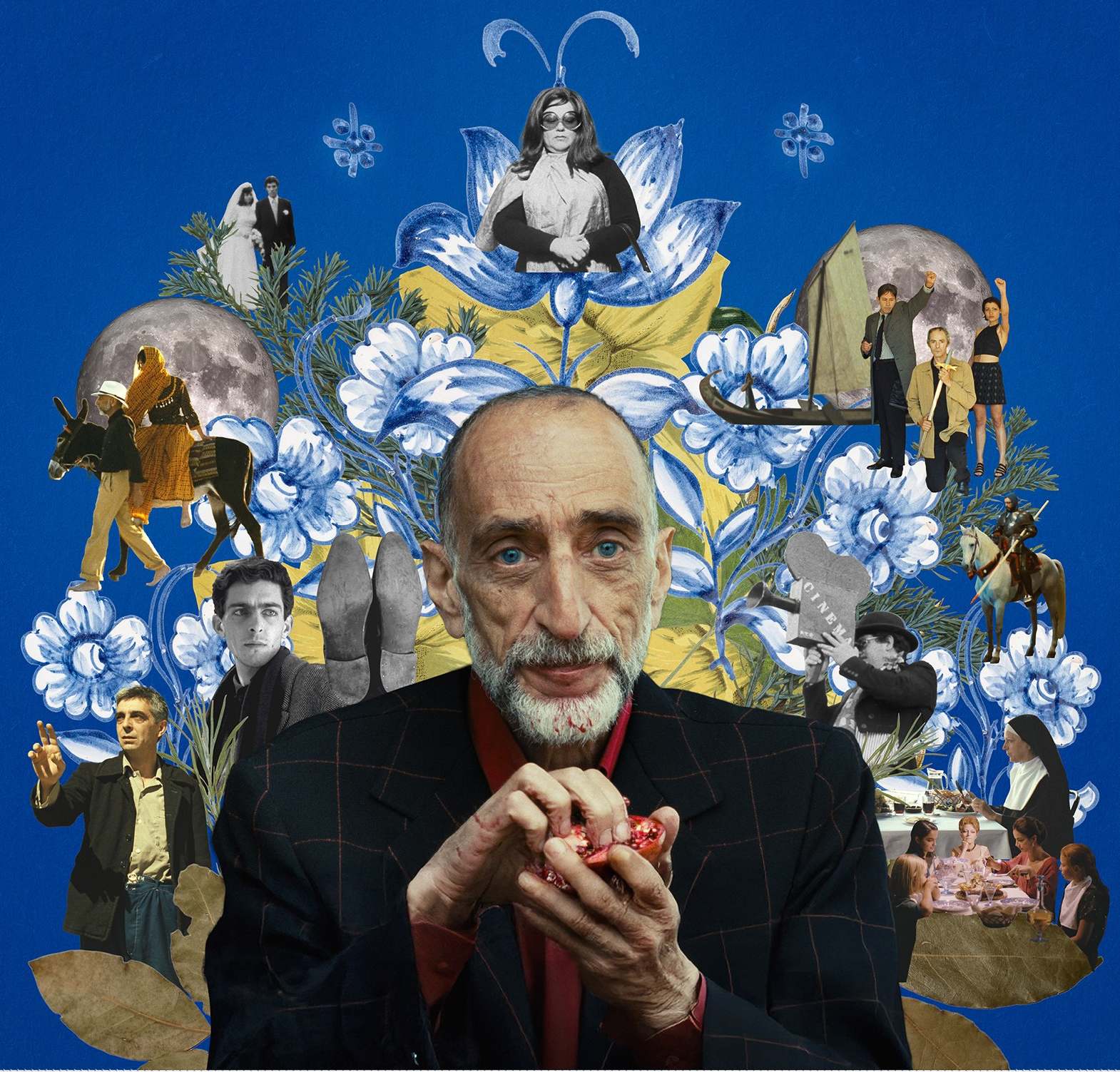

Obras de referência da cultura portuguesa

"GUERRAS DO ALECRIM E MANGERONA"

de ANTÓNIO JOSÉ DA SILVA, "O JUDEU"

Análise de Duarte Ivo Cruz

Tradução de Alexandra Leitão

O valor simbólico desta peça do Judeu transcende em muito o seu próprio conteúdo dramático e mesmo a leitura imediata do texto e do espetáculo. E até se pode ver nela a mais rebuscada e poderosa ação de simulação e de criticismo elíptico que, por razões óbvias de existência tumultuada e de trágico desfecho, marcam a vida, a obra e a morte de António José da Silva.

Não se pode por isso entender as Guerras como um fútil exercício de jogos florais e de amores desencontrados de cariz setecentista, próxima da florescente, na época, produção das comédias chamadas de cordel. É muito mais do que isso, sem deixar de ser, também, um modelo dos aspetos mais positivos de tudo o que acima se escreveu.

Mas em primeiro lugar, há que enquadrar as peças na estética peculiar do teatro barroco, com a dimensão espetacular que a qualificação envolve, e que o cruzamento com a música, original ou recuperada, de António Teixeira mais sublinha. Aliás, essa componente musical das peças ou óperas do Judeu inscreve-se com clareza no delírio operático que dominou a Corte e mesmo o público em geral. De assinalar que foram representadas em Lisboa no Teatro do Bairro Alto: mas ficou a tradição de D. Miguel, um século depois, cantar árias do D. Quixote no teatro improvisado no Palácio de Queluz.

Também é interessante analisar a excecionalidade das «Guerras» no conjunto da dramaturgia do Judeu no ponto de vista do temário. É que, como sabemos, as peças, pelo menos as que não oferecem dúvidas quanto à autoria, dramatizam temas mitológicos ou clássicos. Menos as Guerras, cena galante do setecentismo, guerras de flores ou «ranchos», mas nem por isso menos elíptica na sua mensagem mais ou menos oculta. E esse ocultismo elíptico ainda seria mais reforçado pela utilização de bonifrates, em vez de atores «humanos»...

Porque a grande chave secreta deste teatro está, precisamente, nesse ocultismo elíptico e secreto, que decerto ajudou ao paradoxo da sobrevivência das peças ao longo do terrível processo que levou à execução do autor.

E mesmo assim o conteúdo terá algo de subversivo ou de angustioso no seu criticismo aparentemente risonho, superficialmente vasado num registo de comédia. As rivalidades em torno das flores são muito mais profundas do que parece - sem embargo de outras peças, e designadamente a Esopaida ou Vida de Esopo, ir nisso mais longe, na história do que nasceu escravo e, pelo se mérito exclusivo, acabou Governador de Atenas.

Ou por outras palavras que já usamos noutro local: a linguagem das flores, subtítulo de "Dona Rosita" de Lorca, e os amores grotescos, são sinais e chave da vida secreta, dupla que António José da Silva teve de levar. Sinais de uma tragédia de que o pobre Judeu foi vítima e é imorredoiro documento.

Ainda um aspeto muito relevante: nascido no Rio de Janeiro em 1705, executado pela Inquisição em 1739, não só é o primeiro grande dramaturgo de ligação entre Portugal e Brasil - e insista-se no qualificativo de grande, pois desde Anchieta que houve teatro cá e lá - como está ligado ao início do Romantismo no teatro brasileiro, com a peça de Gonçalves de Magalhães chamada precisamente "António José ou o Poeta e a Inquisição". Esta estreou no Rio em 1838, meses antes da estreia, em Lisboa, de "Um Auto de Gil Vicente", de Garrett, essa considerada, como bem sabemos, a obra iniciática do romantismo no teatro português.

Acima se disse que as "Guerras" se enquadram numa estética do barroco. E que se harmoniza com o teatro de cordel, num registo ocultista e profundo nos temas e de superior qualidade no tratamento dramático e textual. Mas com tudo isto, encontramos lá sinais de uma ainda vaga mas já identificável expressão que iria desembocar, 100 anos depois, no romantismo teatral português.

"GUERRAS DO ALECRIM E MANGERONA" by ANTÓNIO JOSÉ DA SILVA, "O JUDEU"

The symbolic value of this play by da Silva greatly transcends its dramatic content and even a first reading of the text and the play. It even contains a complicated and powerful action of simulation and elliptical criticism which, given his obviously tumultuous existence and tragic ending, marked the life, work and death of António José da Silva.

Accordingly, we cannot read Guerras as a futile exercise of 18th century floral games and chequered loves close to the then flourishing production of so-called romances de cordel or romance novels. The play is much more than this but also a model of the more positive aspects of all that is written above.

In the first place, however, we must the plays in the framework of the particular aesthetic of Baroque theatre, with the spectacular dimension implied by its classification, further underlined by the music of António Teixeira, whether original or recuperated In fact, this musical component of da Silva’s plays or operas is clearly inscribed in the operatic madness that dominated the Court and even the general public. Note that these plays were staged in Lisbon at the Teatro do Bairro Alto: but tradition has it that a century later King Miguel sang arias from Don Quixote at the improvised theatre at the Palace of Queluz.

It is also interesting to analyse the exceptional nature of Guerras in terms of da Silva’s output from the point of view of the subject matter. As we know, these plays, or at least those that raise no doubts as to their authorship, dramatise mythological or classical themes. Guerras is the exception, being a gallant scene of 18th century life, depicting wars of flowers or “ranchos” (factions), but no less elliptical in its more or less hidden message. And that elliptical occultism is further reinforced by the use of puppets instead of “human” actors.

The significant secret key to this play lies precisely in that elliptical and secret occultism which no doubt helped to explain the paradox of how these plays survived throughout the terrible process that led to the author’s execution.

Even then the content is somewhat subversive or tormenting in its apparently playful criticism, superficially spoken in a comical vein. The rivalry between the flowers is much deeper than it appears – despite the fact that other works, namely the Esopaida ou Vida de Ésopo, went much further in this by telling the story of one who was born a slave and through his merit alone became Governor of Athens.

In other words, which we have employed elsewhere: both the language of flowers, the subtitle of Lorca’s Dona Rosita, and the grotesque passions are the signs and the key to the secret double life that António José da Silva had to lead. Signs of a tragedy that victimised the poor Jew and that constitutes an immortal document.

One further relevant aspect: having been born in Rio de Janeiro in 1705 and been executed by the Inquisition in 1739, da Silva is not only the first great playwright connecting Portugal and Brazil – and I insist on the qualifying adjective great, because since Anchieta’s time the theatre has existed in both countries – but he is also linked to the start of Romanticism in Brazilian theatre, with the play by Gonçalves de Magalhães precisely entitled António José ou o Poeta e a Inquisição. It opened in Rio in 1838, months before the opening night in Lisbon of Um Auto de Gil Vicente by Almeida Garrett, which was considered the first Romantic work in Portuguese theatre.

We said above that the framework of "Guerras" is found in a Baroque aesthetic and that it harmonises with romantic theatre, in an occultist and deep register of the themes and of the excellent quality of its dramatic and textual treatment. With all this, however, we find signs in it of a nebulous but already identifiable expression that would lead one hundred years later to Portuguese theatrical romanticism.

Obras de Referência da Cultura Portuguesa

projeto desenvolvido pelo Centro Nacional de Cultura

com o apoio do Ministério da Cultura

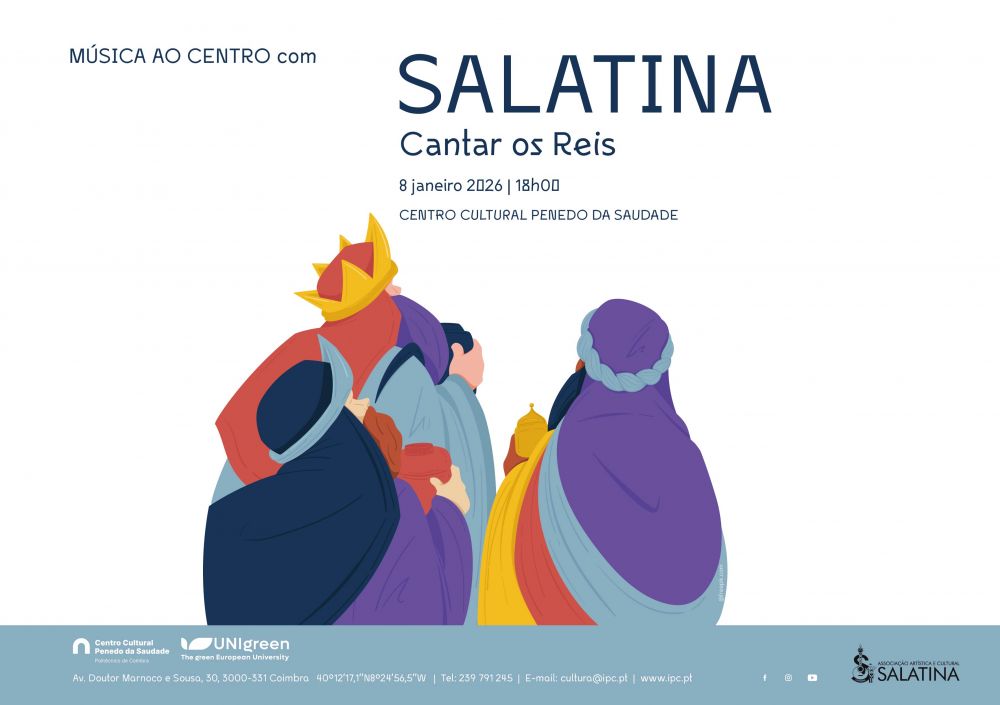

Divulgue aqui os seus eventos

Divulgue aqui os seus eventos