Obras de referência da cultura portuguesa

"MEMORIAL DO CONVENTO"

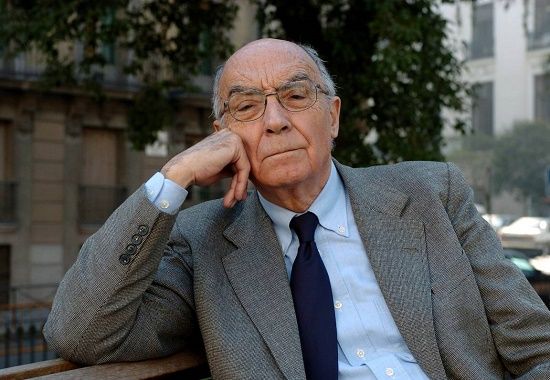

de JOSÉ SARAMAGO

Análise de Miguel Real

Tradução: Alexandra Leitão

Publicado em 1982, Memorial do Convento, de José Saramago (1923), constitui-se como um dos melhores romances históricos portugueses do século XX. Desenvolvendo-se classicamente por via de personagens antitéticas (D. João V / Baltazar Sete-Sóis; rainha D. Maria Ana / Blimunda Sete-Luas; frei António de S. José / Bartolomeu de Gusmão; nobreza e clero / povo de Mafra), Memorial do Convento ganha no entanto a sua especificidade estética através (1) da assunção de uma especial consciência da história da Portugal como suporte da narração; (2) do estatuto ambíguo do narrador, simultaneamente individual e coletivo, circunstancial e intemporal; (3) do estilo original de José Saramago, subvertor da sinalética gramatical e do tradicional lugar do diálogo no seio do texto; (4) da galeria de personagens trágicas e maravilhosas, aproximando o romance português do “realismo mágico” latino-americano, e (5) do conjunto de símbolos que envolvem o texto, prestando-lhe uma força mítica.

Como romance histórico, Memorial do Convento desconstrói a habitual narração da História de Portugal fundada na evolução e transformação das instituições políticas, prestando ao coletivo popular e a personagens humildes (como Baltazar e Blimunda) o papel épico tradicionalmente atribuído ao herói nacional. Do mesmo modo, o estatuto do narrador desdobra-se pelas variadas técnicas e pelos vários sujeitos narrativos estandartizados, a todos estilhaçando, ultrapassando-os e estabelecendo na prática textual um novo sujeito narrativo, à uma histórico e majestático, auto e hetero-diegético, distanciado e participante, pessoal e coletivo, omnisciente e íntimo, ora vocalizado na terceira pessoal do singular, ora na primeira do plural, sujeito que António José Saraiva, à falta de outro termo, identificou com a vox populi ou a vox dei.

Neste sentido, enquanto majestático e omnisciente, o narrador domina o tempo histórico, conhecendo o futuro e revelando proplepticamente as grandes linhas por que a História se desenvolve e o final global a que estas conduzem. Predomina, assim, em Memorial do Convento, o domínio narrativo do tempo, um tempo uno, íntegro, permitindo que o passado, o presente e o futuro sejam perspetivados segundo uma só dimensão textual, deslocando-se a história entre o passado e o futuro como se sempre habitasse o presente. No entanto, escapa a esta omnisciência narrativa a contingência dos destinos singulares e, principalmente, o resultado do entrecruzamento infinito dos atos particulares no seio da história geral. Deste modo, Memorial do Convento, texto uno mas plural, tanto ganha um sentido profético quanto sentencial, tanto é uma história de amor quanto um relato fabuloso, tanto é uma narrativa histórica de feição épica popular quanto um romance confessional, intimista, tanto é uma história iluminista, desmascaradora de crenças supersticiosas, quanto um texto moralista sobre a condição popular.

Na descrição e na narração, José Saramago usa um duplo aspeto estilístico: um leve tom jocoso-parodístico, que satiriza e ridiculariza o modo tradicional de se estudar História, é atravessado por uma história trágico-maravilhosa. Saramago escreve brincando com as palavras e, brincando, narra acontecimentos sérios. Por isso, o lado jocoso de Memorial do Convento não significa gratuitidade; significa, antes, uma apresentação patética (pathos), emocionada, de uma realidade histórica dramática. O pathos lírico da narração, que inspira e encanta, une-se assim à piedade, à comiseração que o leitor sente pelo destino das personagens que são implacavelmente (Baltazar, Blimunda Bartolomeu de Gusmão, Álvaro Diogo, Francisco Marques) arrastadas para um fim trágico. O lado jocoso-parodístico por que Saramago satiriza as personagens da aristocracia torna o romance um quase anedotário, mas um anedotário exemplar, desconstruindo rituais sociais que, na sua nudez narrativa, se evidenciam como ridículos, antes de mais a promessa sobre a qual o convento se levanta, e, depois, a megalomania de D. João V. Neste sentido, devido ao elemento moralista ou exemplar presente em Memorial do Convento, o tom jocoso do estilo torna-se sério, o patético evidencia-se como dramático e o cómico, se comparado com os costumes e a força popular, transfigura-se em épico. Eis o estilo de Memorial do Convento: um cruzamento estilístico entre o jocoso-sério, o patético-dramático e o cómico-épico.

Como romance histórico, Memorial do Convento realiza, igualmente, a suprema harmonia entre um fundo histórico factual e circunstanciado e um nível ficcional, que impera e determina o primeiro, gerando uma síntese unitiva superior, seja através da instância narrativa, seja através da caracterização fabulosa das personagens, seja, ainda, através do maravilhoso da história narrada. Com efeito, as três personagens principais (Baltazar, Blimunda e Bartolomeu de Gusmão) desenham um quadro harmónico fundado no maravilhoso - Blimunda é mais do que uma simples mulher do povo, possui dons extraordinários herdados da mãe; Baltazar, maneta, aparentemente menos do que um homem normal, torna-se mais do que humano ao construir a passarola e ao nela voar, vendo pela primeira vez o mundo “de cima”, do céu, como se fosse Deus, e Bartolomeu de Gusmão evidencia-se como um homem de sonhos visionários, proféticos, que constrói o futuro em forma de estradas no céu e passarolas nelas voando. Porém, são as características sobre-humanas das três personagens que, falhando a normalidade social, as conduzirão à tragédia - Baltazar morrerá queimado pela Inquisição, Bartolomeu de Gusmão morrerá louco em Toledo e Blimunda arrastar-se-á pelos caminhos de Portugal, solitária, guardando o seu segredo visionário.

Memorial do Convento é igualmente habitado por símbolos-força, como o algarismo “sete”, o par “Lua/Sol”, o símbolo da ascensão da “montanha” (a serra de Monchique), o voo da passarola, que, narrativamente, funcionam como operadores míticos do texto, elevando-o a intriga diegética ao estatuto de uma história maravilhosa, reproduzindo potencialmente, no inconsciente do leitor, a força atrativa dos mitos permanentes da humanidade: o desafio do desconhecido, a ascensão ao Sol, o poder mágico da Lua, a imitação dos anjos voando sobre o mundo, o roubo prometaico dos poderes divinos. Porém, subvertendo a condição clássica, o quadro épico desenhado não intenta atingir um estatuto de poder ou de conhecimento semelhante ao dos deuses ou de Deus, mas, apenas, fundar o homem na sua humanidade, libertar o homem de todas as condições servis que o amarram, evidenciando-o na sua mais profunda igualdade: permitir que todos os homens sejam reis e todas as mulheres rainhas.

"MEMORIAL DO CONVENTO" by JOSÉ SARAMAGO

Memorial do Convento by José Saramago (b. 1923) was published in 1982. It is one of the best Portuguese historical novels of the 20th century. Classically developed by means of antithetic characters (D. João V/Baltazar Sete-Sóis; Queen D. Maria Ana/Blimunda Sete-Luas; friar António de S. José/Bartolomeu de Gusmão; nobility and clergy/people of Mafra), Memorial do Convento nevertheless acquires its aesthetic specificity through (1) the assumption of a particular awareness of the history of Portugal as the backbone of the narrative; (2) the narrator’s ambiguous status, simultaneously individual and collective, circumstantial and timeless; (3) José Saramago’s original style, subverting grammar and the dialogue’s traditional place in the text; (4) the gallery of tragic and marvellous characters, bringing the Portuguese novel closer to the “magical realism” of Latin America, and (5) the set of symbols that involve the text, giving it mythic force.

As a historical novel, Memorial do Convento deconstructs the usual narration of the history of Portugal based on the evolution and transformation of the political institutions, giving the epic role traditionally attributed to the national hero to collective people and humble persons (such as Baltazar and Blimunda). Similarly, the status of the narrator unfolds through the varied techniques and the various standardized narrative subjects, shattering them all, overtaking them and establishing in the textual practice a new narrative subject, at once historic and majestic, auto and hetero-narrative, aloof and participative, personal and collective, omniscient and intimate, either vocalised in the third person singular or in the first person plural, a subject that António José Saraiva, lacking another term, called vox populi or vox dei.

So, being majestic and omniscient, the narrator dominates the historic time, knowing the future and proleptically revealing the great lines along which history develops and the global end to which they lead. In Memorial do Convento, then, the narrative command of time predominates, a time that is one, entire, allowing the past, the present and future to be seen from one single textual dimension, the story moving between past and the future as if it always lived in the present. Nevertheless, the contingency of singular destinies and above all the result of the infinite crossing of particular acts within the general story escape this narrative omniscience. So, Memorial do Convento, a united but plural text gains not only prophetic but sentential meaning, it is both a love story and a fabulous tale, a historic narrative of popular epic feats and an intimate confessional novel, an illuminist story that unmasks superstitious beliefs and a moralist text on the popular condition.

In the description and the narration José Saramago uses a double stylistic aspect: a light jocular and parodying tone that satirises and ridicules the traditional form of studying history, is cut across by a tragic and marvellous story. When Saramago writes he is playing with words and whilst playing he narrates serious events. Therefore the jocose side of Memorial do Convento does not signify gratuitousness; rather it signifies an emotional and pathetic (from pathos) presentation of a dramatic historic reality. The lyrical pathos of the narration which inspires and enchants is thus linked to the pity and the commiseration that the reader feels for the fate of the characters (Baltazar, Blimunda Bartolomeu de Gusmão, Álvaro Diogo, Francisco Marques) who are implacably dragged to a tragic end. The jocose and parodying side with which Saramago satirises the aristocratic characters makes the novel almost a book of anecdotes, but exemplary, deconstructing social rituals that in their narrative nakedness are shown to be ridiculous, beginning with the promise on which the convent is built and then King João V’s megalomania. Given the moralist or exemplary element present in Memorial do Convento, the jocose tone of the style becomes serious, the pathetic becomes dramatic and, compared to customs and popular force, the comic becomes epic. This is the style of Memorial do Convento: a stylistic cross between jocose and serious, pathetic and dramaturgic, comic and epic.

As a historical novel, Memorial do Convento also accomplishes the supreme harmony between a factual historical background and a fictional level, which towers over and determines the former, generating a superior unitive synthesis, either through the narrative instance, through the fabulous characterisation of the characters or even through the wonder of the narrated story. In fact, the three main characters (Baltazar, Blimunda and Bartolomeu de Gusmão) depict a harmonious picture based on the marvellous - Blimunda is more that just a simple peasant woman, she has extraordinary gifts inherited from her mother; one-armed Baltazar, apparently less than a normal man, becomes more than human when he builds the aerostat and flies in it, for the first time seeing the world from “above”, from the sky, as if he were God, and Bartolomeu de Gusmão stands as a man of visionary, prophetic dreams, a man who builds the future in the form of roads to heaven and aerostats flying along them.

However, it is the superhuman characteristics of the three characters that, failing social normality, will lead them to tragedy - Baltazar is burned to death by the Inquisition, Bartolomeu de Gusmão dies insane in Toledo, and Blimunda shuffles around Portugal, alone, awaiting her visionary secret.

Memorial do Convento is also inhabited by forceful symbols, such as the number “seven”, the “Moon/Sun” pair, the symbol of climbing the “mountain” (the Monchique mountain range), the flight of the aerostat, which function as mythical operators of the text, raising the narrative intrigue to the status of a marvellous story, potentially reproducing in the reader’s subconscious the attractive force of mankind’s permanent myths: the challenge of the unknown, the ascension to the Sun, the magical power of the Moon, the imitation of the angels flying over the world, the Promethean theft of divine powers. However, subverting the classical condition, the epic picture drawn does not intend to reach a status of power or knowledge similar to that of the gods or of God, but merely to blend man with his humanity, to free man from all the servile conditions that tie him, highlighting the greatest equality: allowing all men to be kings and all women to be queens.

Obras de Referência da Cultura Portuguesa

projeto desenvolvido pelo Centro Nacional de Cultura

com o apoio do Ministério da Cultura

Divulgue aqui os seus eventos

Divulgue aqui os seus eventos