Obras de referência da cultura portuguesa

"PAINEL DO INFANTE D. HENRIQUE"

de NUNO GONÇALVES

Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, Lisboa

Análise de Rui-Mário Gonçalves

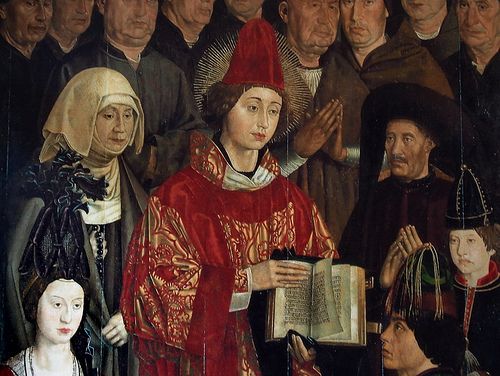

Tradução: Paul Bernard

Este painel faz parte de um políptico constituído por seis painéis que foram encontrados em 1882 no Mosteiro de S. Vicente de Fora, em Lisboa. O mestre que realizou tão prodigiosas pinturas deve ter sido Nuno Gonçalves (c. 1438-1481), pintor do rei D. Afonso V, entre 1450 e 1472. Foram concebidas, assim como mais algumas, para o retábulo da capela dedicada ao mártir S. Vicente, na Sé de Lisboa, cerca de 1470, e depois transferidas para o Mosteiro de S. Vicente de Fora, por ocasião da ocupação filipina (1580-1640). Dado o estado de abandono em que foram encontradas, tem sido difícil aos especialistas da arte quatrocentista concordarem quanto à sua seriação e até quanto à iconografia. O painel aqui reproduzido tem sido designado por “o painel do Infante D. Henrique”, pois aí aparece a figura do grande empreendedor das descobertas marítimas, tal como aparecera num livro de Gomes Eanes de Zurara “Crónica da Guiné”, com o seu chapéu de abas largas.

Considerando o conjunto das tábuas, verificamos que constituem uma inovadora conceção de retrato coletivo, apresentando seis dezenas de rostos de forte carácter, perfeitamente individualizados, cobrindo uma vasta gama da sociedade portuguesa, príncipes, guerreiros, pescadores, frades e letrados, em veneração do santo. O historiador francês René Huyghe afirmou que “na arte de Nuno Gonçalves e da sua escola, há, além do contributo do seu génio, a realização de uma nova etapa da alma ocidental que parte à conquista de si própria (…), pela primeira vez o homem moderno define-se antes de mais como indivíduo: o homem moderno nasceu (…)".

Pode portanto afirmar-se que, quando, no século quinze, a Europa erudita construía a sua mais peculiar metodologia da representação do mundo visível, os pintores portugueses davam uma contribuição fundamental, avançando na afirmação do valor da vontade humana. E esta é a mensagem que imediatamente se apreende nas tábuas de Nuno Gonçalves, onde se pode observar que assumiram a continuidade da aposta política de 1385, também esse considerado geralmente um acontecimento histórico de notável modernidade.

A nova metodologia pictural europeia não surgiu inopinadamente na sua totalidade. Foi sendo construída lentamente, etapa por etapa, de Giotto a Rafael, em Itália, e por outros, no centro e norte da Europa: a opacidade das figuras e sua sobreposição, a unidade de iluminação e a sugestão de relevos, a cor local e a diferenciação das texturas, a correção anatómica e as proporções naturais, o desenho minucioso e a perspetiva linear… Tudo isto existe já na pintura de Nuno Gonçalves, mas como montagem dos dados das etapas enunciadas e ainda não completamente como unidade “naturalista”. Assim, pode reparar-se que nos três planos em que aparecem os rostos não verificamos a diminuição dos tamanhos aparentes destes, tal como a perspetiva linear exigiria: são rostos sensivelmente do mesmo tamanho, os que estão “longe” e os que estão “perto”. Compare-se o rosto do Infante com os dos que lhe estão atrás. Há uma separação brusca entre o espaço vazio junto ao chão e o espaço todo cheio na parte superior, onde as personagens se conglomeraram. As roupagens do santo estão rebatidas para a frontalidade, destacando os padrões do tecido, em contraste com as volumetrias e relevos das roupagens dos outros. Em suma: como “montagem”, a pintura adquire a nitidez de uma escrita de imagens que não abdica de algumas características góticas para melhor clareza expositiva.

"PRINCE HENRY PANEL" ATTRIBUTED TO NUNO GONÇALVES

National Ancient Art Museum, Lisbon

This panel is part of a polyptych of six panels found in 1882 in the Monastery of St. Vincent outside-the-walls in Lisbon. The master who produced such prodigious paintings must have been Nuno Gonçalves (c. 1438-1481), court painter of King Afonso V between 1450 and 1472. They were conceived, together with some others, for the altarpiece of the chapel dedicated to the St. Vincent the Martyr in the Cathedral of Lisbon around 1470, and were later transferred to the monastery of St. Vincent outside-the-walls on the occasion of the Philippine occupation (1580-1640). Given the state of abandon in which they were found it has been difficult for specialists on 15th c. art to agree on the order of the panels and even their iconography. The panel here reproduced has been named the “Prince Henry Panel” as it features the figure of the great entrepreneur of the maritime discoveries just as he had appeared in a book by Gomes Eanes de Zurara, the “Crónica da Guiné (The Guinea Chronicle)”, wearing his wide-brimmed hat.

In contemplating the set of panels, we can verify that they constitute an innovative concept in collective portraiture, presenting as they do five dozen faces of marked character, perfectly individualised, covering a wide range of Portuguese society from princes to warriors, fishermen, friars and men of letters, in veneration of the saint. The French historian Renê Huyghe stated that in the “art of Nuno Gonçalves and his school, there exists, in addition to the contribution of his genius, the realisation of a new stage in the western soul in its search to conquer itself […], for the first time modern man defines himself foremost as an individual: the modern man is born,” […].

One may therefore state that when, in the 15th c., erudite Europe built its most distinct methodology of representation of the visible world, Portuguese painters made a fundamental contribution and advanced the affirmation of the value of the human will. And this is the message one immediately learns in the panels of Nuno Gonçalves, where one can observe that they assumed the continuity of the 1385 political movement, also generally considered a historical event of notable modernity.

The new European pictorial methodology did not emerge unexpectedly in its whole. It was slowly constructed, stage by stage, from Giotto to Rafael in Italy, and by others, in the centre and north of Europe: the opacity of the figures and their superposition, the unity of the illumination and suggestion of reliefs, the local colour and differentiation of the textures, the anatomical precision and natural proportions, the minute drawing and linear perspective... All of this already exists in Nuno Gonçalves’ painting, but as a montage of the data of the aforementioned stages and not yet completely as a “naturalist” unit. Thus, one can notice that on the three planes upon which the faces appear we are unable to verify any diminishment of their apparent sizes as the linear perspective would demand: they are faces perceptively of the same size, those that are “further” and those that are “nearer”. One may compare the face of the Prince with those of the persons behind him. There is a brusque separation between the empty space at ground level and the wholly filled space at the top where the characters come together. The clothing of the saint is struck forward, highlighting the patterns of the cloth, in contrast to the volumes and reliefs of the clothing of the others. In sum: as a “montage” the painting acquires the clarity of a series of images that do not abdicate from some Gothic characteristics to achieve better exhibitive clarity.

Obras de Referência da Cultura Portuguesa

projeto desenvolvido pelo Centro Nacional de Cultura

com o apoio do Ministério da Cultura

Divulgue aqui os seus eventos

Divulgue aqui os seus eventos