Obras de referência da cultura portuguesa

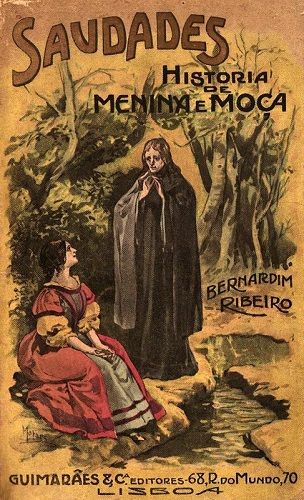

"MENINA E MOÇA"

de BERNARDIM RIBEIRO

Análise de Miguel Real

Tradução: Alexandra Leitão

Entre a primeira e a segunda metades do século XVI o génio fáustico de Gil Vicente alegrava a corte, satirizando fidalgos e frades, Sá de Miranda, homem de uma só fé, exilava-se no Minho, distanciando-se das intrigas e rancores da corte, Camões e Fernão Mendes Pinto peregrinavam pelos longes do Oriente, expiando nas suas vidas as dores de um Império transformado em empório, e Bernardim Ribeiro, como que sofrendo na alma o bloqueio institucional de Portugal (Inquisição, contínuos empréstimos externos à Coroa, fracasso da reforma humanista da Universidade de Coimbra, expulsão de judeus e realização dos primeiros autos-de-fé), antecipando em quatro séculos Fernando Pessoa, exilava-se dentro de si próprio, concentrando na sua obra a totalidade da tradição da literatura portuguesa (cantigas de amigo e de amor, novela de cavalaria, novela pastoril, poesia lírica), ostentando-se melancolicamente, enquanto reflexo cultural do estado de Portugal, como primeiro escritor português dividido “entre mim mesmo e mim”.

A História de Menina e Moça (1ª edição em Ferrara, Itália, em 1554, nos prelos do judeu português Abraão Usque; 3ª edição em Colónia, em 1559, edições destinadas a público judaico e com um final abrupto) ou Saudades (2ª edição em Évora, em 1557, com um fim apócrifo), novela sentimental, de teor psicológico, consolida, face à complexidade de sentidos do seu conteúdo, assente na fatalidade trágica dos amores narrados, a conceção de saudade como sentimento nacional, sentimento que, ontem como hoje, melhor reflete a profunda divisão do Portugal consigo próprio desde o reinado de D. João III, expressão da divisão de cada português consigo próprio. Por via de amores fracassados, interrompidos ou de solução adversa aos amantes, Menina e Moça ou Saudades cristaliza o sentimento de divisão presente na mentalidade portuguesa desde a segunda metade do século XVI, tanto da lembrança ridente do passado quanto da saudade de um futuro sonhado como prolongamento auspicioso do passado.

Quem teria praticado os efeitos nefastos que desviaram o país do seu anterior expansivo e ridente destino? O pronome “eles” é a resposta dada pelo primeiro parágrafo do livro: “Menina e moça me levaram de casa da minha mãe para muito longe”. As causas e o sujeito de quem separou a menina de sua mãe, como Portugal do seu destino, não têm rosto, nem no tempo do autor, que em vida assistia ao esboroamento do Império, como no nosso tempo, que fragmentamos as culpas por um vago centralismo estatal e uma igreja pura de fé e de costumes, bem como pela perda da independência em 1580, verdadeiramente mais consequências do que causas. Tão misteriosa é a nossa decadência que, lida pelos olhos poéticos de Bernardim Ribeiro, se estatui como da ordem da inexorabilidade divina – um fatalismo que se cumpre em trágico destino: “Que causa fosse então daquela levada, era ainda pequena, não o soube. Agora não lhe ponho outra senão que parece que já então havia de ser o que depois foi [fatalismo trágico]”.

Nenhum começo de livro da história da literatura portuguesa cala tão fundo no imaginário português como este de Menina e Moça, primeiro, revelando uma abertura ao horizonte da saudade tanto como recordação bela e amarga do passado quanto como criação imaginosa do futuro, e, segundo, expressa aceitação de um destino providencial que, fasto ou nefasto, encontra na misteriosa vontade de Deus o seu último sentido.

Livre triste, Menina e Moça é o primeiro diálogo introspetivo de Portugal consigo próprio, queixando-se de amores desencontrados, isto é, de, a partir da segunda metade do século XVI, fatigadamente nunca acertar o passado vivido com o futuro desejado.

"MENINA E MOÇA" – YEARNING (SAUDADE) by BERNARDIM RIBEIRO

Between the first and second halves of the 16th century the Faustian genius of Gil Vicente brightened the court, satirising courtiers and friars; Sá de Miranda, man of one faith, exiled himself in Minho, distancing himself form the intrigue and malice at court; Camões and Fernão Mendes Pinto wandered through the distant East, expiating in their lives the pain of an Empire transformed into an emporium; and Bernardim Ribeiro, as if suffering in his very soul Portugal’s institutional blockage (the Inquisition, the unending foreign loans to the Crown, the failure of the humanist reform of Coimbra University, the expulsion of the Jews and the first autos-da-fé), anticipating Fernando Pessoa by four centuries, took exile within himself, concentrating in his work all the tradition of Portuguese literature (cantigas de amigo and cantigas de amor, novels of chivalry, pastoral novels, lyrical poetry). As the cultural reflection of the state of Portugal he paraded melancholically as the first Portuguese writer divided “between myself and me”.

The story of Menina e Moça (1st edition, Ferrara, Italy, 1554, published by the Jewish publisher Abraão Usque; 3rd edition, Cologne, 1559, both editions aimed at the Jewish public both that came to a sudden end), or Saudades (2nd edition, Évora, 1557, with an apocryphal ending), is a sentimental novel with a psychological bent. In the face of its complex feelings based on the tragic fatality of the loves narrated, it consolidates the idea of yearning (saudade) as a national sentiment, a sentiment that as always, best reflects the profound division of Portugal with itself since the reign of D. João III, expressing the division of each Portuguese with himself. By means of unsuccessful love affairs either cut short or contrary to the lovers’ wills, Menina e Moça or Saudades crystallise the sense of division present in the Portuguese mentality from the second half of the 16th century onwards, both of the cheerful memory of the past and the longing for a future which is conceived as an auspicious extension of the past.

Who performed the evil deeds that took the country from its former expansive and laughing destiny? The pronoun “they” is the answer given in the first paragraph of the book: “As a young girl they took me far from my mother’s house”. The causes, and the subject who separated the girl from her mother, as Portugal from its destiny, have no face, neither during the time of the author, who lived through the crumbling of the Empire, nor in our time, where we apportion the blame between a vague idea of State centralism and the Church pure of faith and customs, and the loss of our independence in 1580, mostly really consequence rather than cause. Our decadence is so mysterious that in the poetic view of Bernardim Ribeiro, it stands as something of divine inexorableness – a fatalism that performs as a tragic destiny: “What the cause was that led her to be taken away so young, I do not know. Now I can find no other but that it had to be so [tragic fatalism]”.

No first line of any book in the history of Portuguese literature strikes as deep in the heart of Portuguese imagination as does Menina e Moça. Firstly, revealing an opening to the horizon of yearning both as a beautiful, bitter souvenir of the past and as the fanciful creation of the future, and secondly, expressing acceptance of a providential destiny that, disastrous or otherwise, finds its ultimate meaning in God’s mysterious will.

It is a sad book this Menina e Moça, and the first introspective dialogue of Portugal with itself, bewailing missed loves, in other words, that from the second half of the 16th century onwards Portugal was unable to conciliate the remembered past with the longed-for future.

Obras de Referência da Cultura Portuguesa

projeto desenvolvido pelo Centro Nacional de Cultura

com o apoio do Ministério da Cultura

Divulgue aqui os seus eventos

Divulgue aqui os seus eventos